с 01.01.2021 по настоящее время

Гана

с 01.01.1993 по 01.01.2019

Сибирский федеральный университет (Базовая кафедра цифровых финансовых технологий Сбербанка, доцент)

с 01.01.2007 по настоящее время

Красноярск, Красноярский край, Россия

ВАК 08.00.10 Финансы, денежное обращение и кредит

ВАК 08.00.12 Бухгалтерский учет, статистика

ВАК 08.00.13 Математические и инструментальные методы экономики

ВАК 08.00.14 Мировая экономика

УДК 336.74 Деньги. Денежное обращение

УДК 336.71 Банковское дело. Банки

УДК 334 Формы организаций и сотрудничества в экономике

Статья посвящена анализу процесса становления и развития бизнес-систем в республике Гана. Для стран с развивающейся экономикой бизнес-экосистема является растущим сектором, как с точки зрения объема, так и экономического воздействия. Статья представляет собой предварительное исследование, в котором рассматривается структура экосистемы, закладывая основу для будущего стратегического анализа. Эмпирической базой исследования послужили материалы банка Ганы, аналитические отчеты банков и платежных систем за период с 2004 по 2020 годы. Для иллюстрации процесса развития, проблем и вызовов, стоящих перед экосистемами, обоснования потребности в ресурсах и причин мотивации страны к созданию собственной бизнес-экосистемы, мы использовали теорию бизнес-экосистемы Мура. На основе комплексного анализа процесса организации экосистемы и опыта других стран мы предложили рекомендации по усилению совместного взаимодействия банков и бизнеса, созданию сетей, повышению открытости (в том числе через раскрытие отчетности), что объединит усилия по созданию мощной бизнес-экосистемы в Гане. Также делается вывод, что в целях государственной безопасности необходимо создать новые регуляторные механизмы для развития бизнес-экосистемы страны.

бизнес-экосистема, мобильные платежи, ресурсные требования, финансовые технологии (FinTech), цифровые ресурсы

Introduction

The way firms are organized across borders has undergone a paradigm shift. Business ecosystems, which are dynamic groups of mainly autonomous partners who work together to offer integrated products and services, are progressively replacing the old model of the integrated organization with its hierarchical supply chain. Such collaborative networks are also becoming more important in addressing the world's most pressing issues. This was impressively demonstrated during the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, when a slew of new ecosystems arose to coordinate health-care services and balance utilization, provide 3D printing capacity for medical equipment production, and develop smartphone apps for virus tracking and protection, among other things.

In developing economies, the formation of business ecosystems has become commonplace. In Ghana, this phenomenon is rapidly gaining traction. It's worth noting that 60 percent of the countries on the World Bank's list of the world's top ten fastest growing economies are on the African continent. Ghana is expected to have the fastest-growing economy in the world in 2019. With the aid of foreign direct investments and the creation and implementation of policies such as the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Plan, the country has created and nurtured one of the strongest startup ecosystems in Africa since 2013. (NEIP). These practical initiatives have surely elevated Ghana's ecosystem's growth to a strategic level.

As a result, the focus of this study will be on the development of Ghana's business ecosystem. This project intends to define a target business ecosystem in Ghana, as well as its components (actors, roles, and interactions). (Ma 2019) proposes a “framework for business ecosystem modeling that contains three sections and nine stages that include theories from system engineering, ecology, and business ecosystem”.

The rest of the paper begins with a discussion of the objectives, followed by an examination of the theoretical framework, the intensity of business ecosystem development, challenges impeding business ecosystem development, resource requirements, and justification for maintaining a homegrown business ecosystem, all of which are based on the rapid growth of MTN Mobile Money in Ghana.

General objective of the study

The major goal of this research is to examine the state of Ghana's business ecosystems.

Specific Objectives:

- to assess the intensity of business ecosystems development in Ghana;

- to assess the challenges inherent in the development of business ecosystem in Ghana;

- to assess the resources required for business ecosystem development in Ghana;

- to assess the justification in support of the country maintaining its own business ecosystem.

Research Questions

In light of the aforementioned research goals, this study aims to address the following questions:

- What is the level of development of Ghana's business ecosystem?

- What are the obstacles to Ghana's business ecosystem's development?

- What resources are required for the development of Ghana's business ecosystem?

- What justifies Ghana's development of its own homegrown business ecosystem?

Theoretical Framework

“The life cycle of a company ecosystem” (Moore, 1996), “ecosystem roles” (Iansiti and Levien 2004; Levien 2004), “S-D” (Service-Dominant) “logic, and value co-creation have all been studied in business ecosystem theories” (Vargo and Lusch, 2016). The term ecosystem has its origins in biology, where it is described as "a system of species occupying a habitat, coupled with those components of the physical environment with which they interact" (New Oxford Dictionary, 1993). From this biological ecosystem approach, as well as the study of business networks, the notion of business ecosystem was born. More (1993), as quoted by Tobin (2011), coined the phrase "business ecosystem," which he characterized as "an economic community sustained by a foundation of interacting organizations and persons - the business world's organisms" (More,1996).

Suppliers, consumers, partners, competitors, and other stakeholders make form the economic community of a company ecosystem. More (1996) “saw the business ecosystem as a tool for understanding how an economic community functions, and claimed that it should take the place of industry”. And that “company should be viewed as part of an ecosystem rather than a single industry” (Moore, 1996). “Extended ecosystem analogies have been developed throughout the previous few decades, with significant examples including the industrial ecosystem” proposed by Frosch & Gallopoulos (1989) and the economy as an ecosystem proposed by Roehrich (2004). The notion that a biological ecosystem is characterized by a large number of loosely connected players who rely on each other for mutual effectiveness and survival is central to all of these parallels (Ianshi & Levien, 2004). And that the ecosystem's species all share the same fate. Ianshi et al. (2004) expanded on the business ecosystem notion, defining it as a business network made up of huge loosely connected networks of businesses interacting in complicated ways. The entities form "hubs," which are groupings of members connected closely and can have an impact on the health of a whole network, and these "hubs," are referred to as "keystones," within bigger networks. In fact, Ianshi et al (2004), like Moore (1993), contended that “no firm can operate in isolation, and that a firm's health and performance are inextricably linked to the health and performance of the entire business community”. They went even farther, proposing robustness, productivity, and niche development as criteria for measuring ecosystem health. “They also devised innovation and operation techniques that a company can use depending on its ecosystem function” (Hartigh & Asseldonk, 2004). They introduced three main responsibilities that businesses can consider as their business ecosystems develop:

- Keystone corporations are those that operate as enablers and have a significant impact on the entire system. Unlike dominators, they do not attempt to control the network; rather, they facilitate access to resources, allowing them to gain from the actions of others. They go with a platform approach. In terms of value creation and sharing, the keystone serves a structural role within its ecosystem (Iansiti & Levien, 2004). As a result, it should be mindful of the influence of its activities on the ecosystem's members and align its interests with those of the rest of the community;

- Niche players, on the other hand, are smaller businesses that make up the majority of the business ecosystem but focus on a narrow range of activities (Suglobov, 2021). They use the keystone's platform to gain access to the keystone's resources and use their particular expertise to add value to the ecosystem. Isckia (2009) contributes to the creation of new inventions and the platform of the keystone. The niche player's demand for a specialized spot within the community leads to real ecosystem advances. The niche player's survival is contingent on the niche player's ability to attract new customers;

- Dominators and hub landlords are organizations that draw resources from the system but do not reciprocate in any way. Dominators are referred to as physical dominators, whereas value dominators are referred to as hub landlords (Isckia, 2009). They have complete control over the other species in their environment and are attempting to take over via vertical integration.

The complexity and unpredictability of the ecosystem would decide the best role methods. The creation of business ecosystems in Ghana is rapidly gaining ground. Ecosystems thinking is a new frame and mentality that represents a significant shift in the economy and business environment. Relationships, partnerships, networks, alliances, and collaborations are obviously important in Ghana, but their value is expanding. The art of the possibility is quickly expanding as it becomes easier for businesses to deploy and activate assets they don't own or control, to engage and mobilize larger and larger groups of people, and to permit far more intricate coordination of their knowledge and actions.

The Intensity of business ecosystem in Ghana

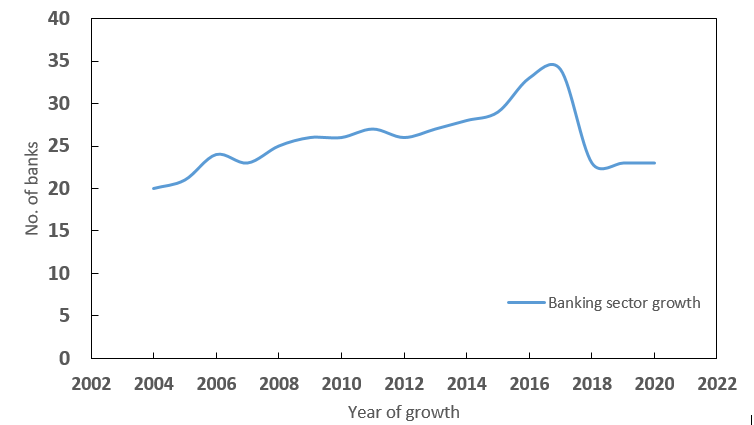

Ghana's commercial ecosystem is dominated by banks for the most part. Almost all of Ghana's 23 licensed banks have created their own ecosystems while also participating in others. Cal Bank, for example, one of Ghana's two indigenous banks, has built a fantastic and robust business environment that has attracted well-known competitive enterprises in Ghana and internationally. Pension firms, insurance companies, government organizations, private health facilities, microfinance companies, motor dealers, IT and internet providers, key automobile industry players, and media companies are only a few of the actors in the Cal bank business ecosystem. The goal of this collaboration is to provide or add value to these firms by improving customer experience while also maintaining their particular company survival. A powerful digital infrastructure underpins this wonderful feet, letting companies to plug in to demonstrate their goods and services. Following the Bank of Ghana's cleanup of the banking sector in Ghana in 2019, Cal Bank has emerged as one of the main financial service providers and one of the few surviving indigenous banks in Ghana. Over the years, Ghana has seen a number of Banks. The figure 1 illustrates the growth in the banking sector over the years.

Figure 1 - Growth in the banking sector since 2004

There has been steadily growth in the banking sector ecosystem in Ghana. There was a sharp in increase in the sector players between 2014 and 2017. The number increased significantly from 28 to 34 licensed banks with Ecobank Ghana been the market leader. However, the intervention from the Bank of Ghana in 2019 to clean the sector of weak financial institutions both banks and special deposit taking institutions occasioned a sharp decline in the number of banks from 34 to 23 as shown in the graph above. This notwithstanding, there has been a significance increase in the total assets of the banks as depicted in chart below;

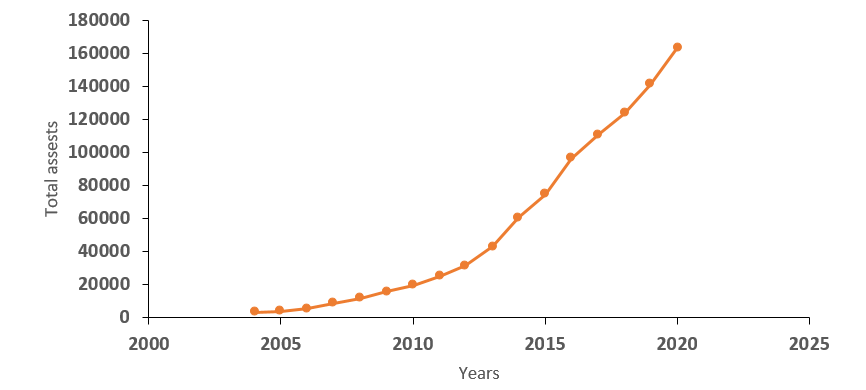

Figure 2 - Growth in total assets of the banking sector

In the year 2020, the banking sector's assets increased by GHC17, 545.99 billion Ghana cedis, or nearly 16 percent, to GHC163,871.11 billion Ghana cedis. Over the last five years, the banking sector has grown at an annual rate of 15% on average. These achievements have been made possible by banks changing their business models, allowing them to collaborate with industry partners and get enormous FinTech support. Since then, the Ghanaian financial industry has performed well. The comparative performance metric of the banks in Ghana is displayed in the table 1.

Table 1 - Performance indicators of the Ghanaian banking industry

|

Year |

ROA |

ROE |

Cost to income ratio |

GDP |

|

2020 |

4.4 |

21.4 |

51.40 |

-2.6 |

|

2019 |

4.1 |

19.9 |

54.8 |

3.1 |

|

2018 |

3.4 |

18.5 |

58.3 |

3.3 |

|

2017 |

3.6 |

18.7 |

59 |

3 |

|

2016 |

3.8 |

17.3 |

57.4 |

1.4 |

|

2015 |

4.5 |

21.4 |

53.20 |

3.9 |

|

2014 |

6.4 |

32.3 |

49.2 |

4.2 |

|

2013 |

6.2 |

30.9 |

48.20 |

7.1 |

|

2012 |

4.8 |

25.8 |

53.8 |

7.9 |

|

2011 |

3.9 |

19.7 |

59.80 |

15.0 |

|

2010 |

3.8 |

20.4 |

58.5 |

7.7 |

|

2009 |

2.8 |

17.5 |

62.80 |

4.00 |

|

2008 |

3.2 |

23.7 |

64.8 |

8.4 |

|

2007 |

3.7 |

25.8 |

62.50 |

6.5 |

|

2006 |

4.8 |

27.5 |

59.3 |

6.2 |

|

2005 |

3.3 |

24.1 |

68.70 |

5.8 |

|

2004 |

4.6 |

22.9 |

63.5 |

5.8 |

Payment System Ecosystem of Ghana

The payment system is a country's whole matrix of institutional infrastructure arrangements and processes that enable economic agents (people, enterprises, organizations, and the government) to originate and transfer monetary claims in the form of commercial and central bank liabilities.

Ghana's payment system has advanced greatly since the introduction of MICR cheques in 1997, and it continues to expand to meet the country's socioeconomic demands. Economic, financial, and public policy issues, as well as a developing local ICT industry and worldwide payment system growth trends, are driving Ghana's present payment system development trend. The development of payment and settlement systems in Ghana has been premised on the following key objectives:

- to prevent and or contain risks in payment, clearing and settlement systems;

- to establish a robust oversight and regulatory regime for the payment and settlement systems;

- to bring efficiency to fiscal operations of the Ghana Government

- to deepen financial intermediation;

- to discourage the use of cash for transactions while encouraging the use of non-paper based instruments;

- to promote financial inclusion without risking the safety and soundness of the banking system; and

- to develop an integrated electronic payment infrastructure that will enhance interoperability of payment and securities infrastructures.

Ghana's payment system now offers a diverse selection of items to the general public. The performance of Ghana's payment system is shown in the table 2.

Table 2 – Comparative Payment System Statistics, 2017-2020

|

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Cheque Code Clearing |

Volume of transactions |

7334460 |

7255220 |

6831417 |

5903331 |

|

GHC’ million |

17955,47 |

203465,32 |

173623,25 |

177625 |

|

|

Gh-LinkTM (National Switch) |

Volume of transactions |

2340409 |

1830182 |

972746 |

806486 |

|

Volume of transactions (GHC’ million) |

603,43 |

543,74 |

329,23 |

329,7 |

|

|

E-Zwich |

Volume of transactions |

8367,02 |

7759354 |

10796560 |

10477601 |

|

Volume of transactions (GHC ’million) |

3434,49 |

5651,14 |

6308,37 |

9033,25 |

|

|

GhIPSS Instant Pay (GIP) |

Volume of transactions |

41759 |

143879 |

1905267 |

6804754 |

|

Volume of transactions (GHC’ million) |

83,23 |

534,04 |

3456,89 |

9146,76 |

|

|

Mobile Money |

Volume of transactions |

981564563 |

1454470801 |

2009989300 |

2859624191 |

|

Volume of transactions (GHC’ million) |

155844,84 |

223207,23 |

309352,25 |

564155,9 |

|

|

ATMs |

Volume of transactions |

57317491 |

57709252 |

55709252 |

56603211 |

|

Volume of transactions (GHC’ million) |

18542,94 |

26392,44 |

26392,44 |

32148,03 |

Participants of Payment Systems

The central bank, commercial banks, service providers, and system users are all stakeholders in Ghana's payment system. In the payment system, the central bank plays a crucial and unique role. It is a payment system overseer, operator, and participant. Commercial banks are part of the system since they make and receive payments on their own behalf or on behalf of their customers. The printers of payment instruments and communications businesses that offer the payment system's infrastructure are the service providers. Regardless of each stakeholder's particular position, they are all users of the payment system, including the banking public.

The Ghanaian FinTech ecosystem

Despite the banks' best efforts to establish themselves as business leaders in Ghana, the Mobile Telecommunication Industry players have established themselves as game changers in the country's business ecosystem development. With the introduction of its flagship product, "MOMO," or Mobile Money, the telcos have pushed the growth of business ecosystems in Ghana. MTN, Ghana's largest company, is responsible for the intermittent expansion of mobile money in the country. Similarly, Financial Technology (FinTech) firms have built more robust ecosystems that bring together a diverse set of participants while adding value to clients and ensuring economic viability.

Financial Technology (FinTech) in Ghana is exploding. In Ghana, the FinTech ecosystem is rapidly moving from "inception to growth." There was a significant dearth of collaboration in the early stages, and interoperability was a distant dream, with each FinTech working in its own bubble, carefully guarding its territory and trade secrets.

Product creation, delivery methods, data analytics, data management, technical support, and system development were all areas where FinTech played a big role in the payment ecosystem. FinTech and financial institution collaboration has increased recently, resulting in the launch of digital savings, investment, credit, insurance, and pension products. The National Communications Authority's completion of an interoperability initiative for Mobile Telecommunications Network Providers in Ghana encouraged the implementation of new mobile merchant point-of-sale solutions and increased demand for FinTech services.

The Bank established a Fintech and Innovation Office (FIO) in 2020 to advance the cash-lite, e-payments, and digitization agenda, as part of its commitment to nurturing a dynamic, inclusive, safe, and efficient digital financial services ecosystem. Dedicated Electronic Money Issuers (DEMIs), Payment Service Providers (PSPs), Payment and Financial Technology Service Providers (PFTSPs), and other developing kinds of payments delivered by non-bank organizations are all regulated by the FIO. In addition, the FIO promotes policy in Ghana to support Fintech innovation and interoperability.

The Bank of Ghana has given its first Dedicated Electronic Money Issuer Licence to Zeepay Ghana Limited, a local Financial Technology (Fintech) business, in compliance with the Payment Systems and Services Act, 2019 (Act 987). Zeepay Ghana Limited has been granted a license to operate as a Dedicated Electronic Money Issuer.

Ghana's FinTech ecosystem is complex and dynamic, having more dynamic interdependencies across firms than anywhere else in Africa (Disrupt Africa, 2019). Actors include government authorities including telecom regulators and the central bank, as well as traditional financial institutions, telcos, merchants, FinTech startups, agents, think tanks and development groups, and users. The links between incumbents (solid line arrows) and new actors are depicted in Figure 3. (broken line arrows).

Figure 3 - The Ghanaian FinTech ecosystem. (Senyo et al , 2022)

The Ghanaian central bank, known as the Bank of Ghana, is a well-established player (BoG). The Bank of Ghana (BoG) controls financial operations by issuing policy and regulatory guidance in order to reduce systemic risk and improve consumer outcomes, such as financial inclusion (Senyo & Osabutey, 2020). The BoG sees FinTech as a vital enabler of successful business ecosystems and financial inclusion, and has established a FinTech and innovation department, as well as policies on e-money and digital financial services, a payment system and services law (Act 987, 2019), and a FinTech licensing scheme to regulate the ecosystem (Senyo et al., 2020).

Traditional financial institutions, such as micro-savings and loan services organizations, were originally Ghana's sole providers of banking services, and were regulated by the Bank of Ghana (BoG) (Senyo et al., 2020). Because telcos are not licensed as independent financial institutions and cannot keep funds in the same way, they now play an important role as custodians of funds transacted on mobile money networks in addition to their main banking services. Each telecom, for example, must have a partner bank to which eFund deposits are transmitted and retained for protection.

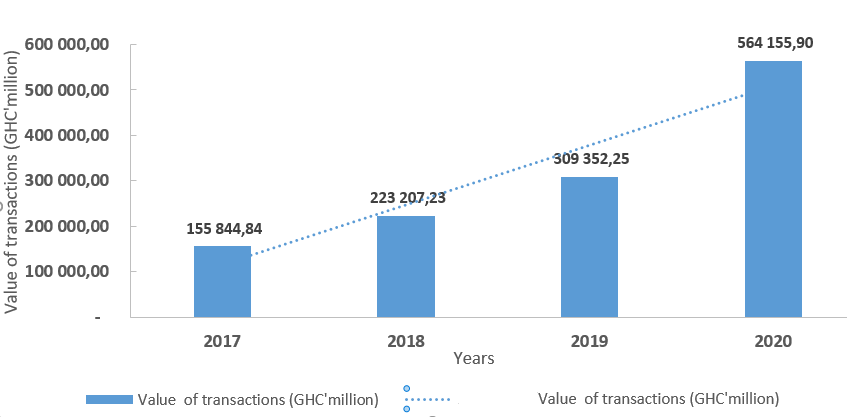

Mobile money services are provided by telcos via their mobile network infrastructure. Telcos perform a vital bridging function in Ghana, as well as much of Africa, by providing a platform for citizens to access financial services. They frequently design and deliver financial services directly (Iman, 2018), and they play a key role in mobile money services (see Figure 3.4). FinTech companies and banks collaborate with telcos to supply mobile money-based financial services. Similarly, while telecoms have limited physical locations, their connections with mobile money agents provide additional entry points. In Ghana, there are over 30 different mobile money services and FinTechs in Ghana, including Qwikloan, Zeepay, G-money, Slydepay, and eTranzact. Again, the value of transactions within the mobile money ecosystem has grown exponentially over the years in Ghana as shown below (Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Growth in Mobile Money Ecosystems Transactions

Since its debut to the market, the figure above depicts the degree of patronage this Mobile Money product has received from the general public. Growth in the value of transactions has been unprecedented in any single business ecosystem in Ghana. The actors in the industry play critical role in the success achieved so far.

Merchants accept mobile money payments for products and services, whereas FinTech companies create digital financial services. FinTech companies provide electronic payments and easy interoperability among actors, as well as the integration of electronic payments via mobile phones into a variety of products and services. As a result, users can execute digital financial transactions.

Agents are actors in the delivery of financial services who are contextually specific to developing countries. Agents in Ghana are small businesses, usually run by a single person, that operate as "shadow bank branches" or "cash-in, cash-out" points, offering digital financial services such cash deposits and withdrawals, mobile money transfers, airtime sales, and mobile money registrations. “Agents have aided in the expansion of financial inclusion in developing nations and provide everyday financial assistance to the majority of populations” (Oborn et al., 2019). Other parties, such as think tanks, offer financial and technological literacy programs and may assist in the development of specialized technologies and policies for the unbanked. Finally, individuals and businesses utilize mobile money to conduct financial activities such as money transfers, bill payments and school fees, phone credit purchases, data bundle purchases, and insurance services. and electricity credits, make deposits and secure micro-loans. As a result, mobile money is gradually replacing cash transactions in Ghana.

The client offers a variety of demands to the mobile money ecosystem as opportunities. A mobile money service's final beneficiaries are its customers. Consumer behavior toward mobile money services determines whether the ecosystem succeeds or fails. As a result, it is critical that mobile money services meet consumer needs and that customers have a positive experience with the services, reducing the risk of carrying cash and increasing access to and affordability of payment, remittance, and other financial services. The table 3 depicts the performance since 2013.

Table 3 - Mobile Money Service Ecosystem snapshot

|

Indicators |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Total number of voice subscription (Cumulative) |

25618427 |

28026482 |

30360771 |

35008387 |

37445048 |

40046590 |

- |

0 |

|

Registered mobile money accounts (Cumulative) |

3778374 |

4393721 |

7167542 |

12120367 |

23947437 |

32554346 |

32470793 |

38500020 |

|

Active mobile money accounts |

345434 |

991780 |

2526588 |

4868569 |

11119376 |

13056978 |

14459352 |

17100533 |

|

Registered Agents (Cumulative) |

8660 |

17492 |

26889 |

79747 |

194668 |

396599 |

306346 |

- |

|

Active Agents |

5900 |

10404 |

20722 |

56270 |

151745 |

180644 |

226298 |

- |

|

Total volume of transactions |

17042241 |

40853559 |

113179736 |

266246537 |

981564563 |

1454470801 |

2009989300 |

2859624191 |

|

Total value of transactions (GHC’ million) |

594,12 |

2652,47 |

12128,89 |

35444,38 |

155844,84 |

223207,23 |

309352,25 |

564155,9 |

|

Balance on Float (GHC’ million) |

19,59 |

62,82 |

223,33 |

547,96 |

2312,07 |

2633,93 |

2,63 |

7000,23 |

Both the value and volume of the mobile money ecosystems has increased tremendously over the years. The prospects are positive for the banking industry. It appears like over 90% of the Ghanaian population are currently using mobile phone and a larger part of them are fast moving to the mobile money platform.

Challenges facing business ecosystems development in Ghana

The establishment of business ecosystems in Ghana, like many other parts of Africa, is fraught with difficulties. Below, we'll go over some of the most pressing issues.

Challenges with management

Sometimes, there's the problem of leadership crises. The topic of business ecosystem management has gotten a lot of interest in the last two or three years. The ability of a company to actively design, shape, and leverage the dynamics of its business ecosystem has become a critical component of competitive advantage, particularly in light of ongoing digital transformation dynamics, which continue to disrupt industries and redefine how business is done in the twenty-first century. Most of the time, the ecosystem's orchestrators have a stronghold on the system. Leaders may have a tendency to literally dictate to players how they should conduct their business, suffocating drive and initiative, which are critical to the long-term viability of the entire business ecosystem. In some cases, the lack of coordination among the many stakeholders in the ecosystem becomes apparent. Their egotistical natures can occasionally expose the system's flaws.

Challenges for the interoperability

The degree of incompatibility of information technologies, such as architectures, platforms, and infrastructure, is a technological difficulty and obstacle for digital business ecosystems. The standards for presenting, storing, exchanging, processing, and communicating data and information from loosely coupled organizations within the ecosystem are among the most common hurdles. ‘The development of digital interfaces, or techniques and standards for data sharing, is still in its infancy” (Chen, Vallespir & Daclin, 2008). SMEs, in particular, have a hard time meeting these basic requirements. There are organizational problems in addition to technology challenges. In terms of decision-making, responsibility, and autonomy, participating organizations have diverse structures and frequently follow different organizational logics. Different semantics, cultures, and communication styles exist. According to recent study, “coherence across decision-making principles can be a key requirement for ecosystem evolvability” (Chen et al 2008, Tsujimoto et al 2017). This coherence appears to be critical for a balanced trade relationship and a minimum of trust between autonomous partners.

Challenges with inadequate policy framework

In addition, the country's policy framework for the business ecosystem is deficient. Even if these policies exist, they are isolated from one another. Existing and potential ecosystem developers will benefit from the availability of a policy framework.

The challenge of thinking differently

Successful businesses have been taught to look within themselves to solve challenges and meet client demands. Rethinking how to respond to client requests and improve services by looking within the ecosystem will be one of the most difficult issues. An ecosystem provides a one-of-a-kind opportunity to gain access to a solution – most likely from a company that specializes in this field – without having to commit time and money into developing it. It's the most effective form of interdependence.

Weak or lack of regulation

The concept of a business ecosystem is gaining traction in the economies of most African countries, including Ghana. The concept of ecosystem is not new in and of itself, but expanding it to corporate relationships is one of the most intriguing concepts to get the attention of regulators. The majority of the players in Ghana's business ecosystem are governed by several regulatory bodies. There are four national regulators in the financial services sector, for example. Banks are regulated by the Bank of Ghana (BoG), pension funds are regulated by the Pensions and Regulatory Authority (NPRA), insurance firms are regulated by the National Insurance Commission (NIC), and investment and fund managers are regulated by the Security and Exchange Commission of Ghana (SEC). There are a slew of other governing bodies. Each of these regulating agencies has its own set of goals and techniques. The emergence of corporate ecosystems, which require these regulatory agencies to collaborate under a shared understanding, philosophies, and strategies in order to maintain the economy's sanity. These bodies already lack a sufficient understanding of challenges occurring in other disciplines, let alone complicated and dynamic corporate innovations brought on by digital disruptions. As a result, numerous regulators are currently embracing the proper tactics to cross-regulate company in order to attract participants from other industries.

Solutions for the challenges

“The most often cited solutions were co-creation, networking, enhancing transparency, and sharing information” (Tobin,2011)

Co-creation, which involves sharing expertise between organizations and merging the skills of many sorts of actors, was deemed promising. The actors should come from all industries and include both small and major businesses.

Connecting with foreign partners (e.g., companies, NGOs) would provide opportunity to develop solutions to the problems outlined. Furthermore, collaboration with domestic partners could be expanded. Networking opportunities would be enhanced through research projects that bring companies together.

Key Resources Required for Ecosystem Business Development in Ghana

The major assets that a business needs to create the end product or value for ecosystem members are known as key resources. The way and what resources are needed, as well as how they are sourced, can have a significant impact on the whole company strategy. The sort of corporate ecosystem has a direct impact on key resources. Apple, for example, designs its computers but does not own the factory that produce them. Key Partners are companies that own facilities and manufacture Apple's laptops, iPhones, iPads, and Macs.

The primary resource requirements for the Ghanaian business ecosystem environment can be divided into five categories. Financial resources, physical resources, intellectual resources, human resources, and digital resources are only a few of them.

- Tangible assets, such as equipment, manufacturing plants, distribution networks, inventory, and other structures. Intel relies heavily on semiconductor plants as a supply of raw materials.

- Intangible assests: Intellectual property, patents, and partnerships are examples of intangible assets. Customer knowledge is also a valuable intellectual resource. While developing these resources takes time and money, they are a significant driver of innovation and growth.

- Human: Organizations in the service, software, finance, scientific, and technology industries use human – employee-related resources. These tools are critical for any company seeking to flourish via creativity and a varied pool of knowledge. To promote its drugs to doctors, pharmaceutical giant Novartis relies on a team of highly qualified scientists and sales professionals.

- Financial - for publicly traded corporations, this includes cash, credit, and stock options. While financial resources are vital in all firms, they are especially important in the banking and insurance industries. An insurance firm with insufficient money to pay out insurance claims, for example, is unlikely to survive.

- Digital resources – these resources are the technology base infrastructure underpinning a vibrant ecosystem in Ghana. They include the software creating a common platform for all the signed on actors to corporate and compete for value creation.

Why Ghana Needs Its Own Business Ecosystems

The case for developing one's own business ecosystem infrastructure rather than relying on foreign base infrastructure is compelling. The need to establish African ecosystems of locally held enterprises has become an undeniable requirement. This is evident in the understanding that creating an efficient and operable environment for businesses and companies is in the best interests of everyone in society.

Telcos, as previously said, are at the forefront of Ghana's economic ecosystem. Mobile Money (MOMO) has been widely adopted thanks to the efforts of telecommunications providers like as MTN, Vodafone, and AirtelTigo, who have provided customers with a fast, simple, convenient, safe, and economical option to conduct financial transactions using their mobile phones. Ghana's telecommunications companies have succeeded in creating one of the largest business ecosystems in the country, if not the entire African continent. However, behind natural resources, telecom is one of the most important monopoly sectors in most developing countries. According to Moore (2003), the majority of telecom providers in Ghana, as in other developing nations, are either state-owned or partially privatized. Some foreign-oriented digital entrepreneurs in the country are technologically and organizationally capable of circumventing these monopolies by setting up their own satellite links to the outside world, routing voice calls over the Internet, and establishing local radio networks to circumvent local connections. These trends put telecom revenues, and consequently government and other telecom investors, in jeopardy.

Furthermore, developing a homegrown ecosystem infrastructure with maximal control in the hands of indigenes - local business with development potential – is a very realistic business strategy. Encouraging local businesses to dominate some of the most important business ecosystems is critical to the government's job-creation objectives. Foreign-owned businesses are typically or primarily profit-driven, with little emphasis on human development and employment creation.

Again, having a robust company ecosystem locally is critical for the country's GDP growth rate. Foreign entities can assist in this area; however, such businesses always act in accordance with their cooperating aims, not necessarily the country agenda. As a result, it makes sense to support local businesses in order to create a great ecosystem. When this is accomplished, the rate of GDP growth becomes even more sustainable.

Finally, FinTech gives more viable potential to improve Ghana's financial inclusion. The importance of financial technology (FinTech) in bridging the gap between the poor and financial services is well acknowledged. Globally established business ecosystems such as Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Uber, among others, are more profit-driven, leaving less profitable endeavors such as financial inclusion operations to fend for themselves. Against this backdrop, the government of Ghana, like its peers in developing economies such as Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, must make steps to encourage the growth of homegrown business ecosystems using a local-led FinTech business ecosystem as the vehicle.

Conclusion

The fundamental difficulties in the development of Ghana's business ecosystem — the intensity, challenges, resource requirements, and justification for full homegrown business ecosystem growth – are outlined in this article. Business ecosystems are defined as the gathering of several participants of all types and sizes in order to build, scale, and serve markets in ways that are beyond the capacity of any single organization—or even any traditional industry. Their diversity—and, more importantly, their ability to learn, adapt, and, most importantly, innovate together—are critical factors in their long-term success. The necessary literature has been reviewed in order to assist the writers in situating the Ghana issue in today's literal thinking. According to the survey, Ghanaian telcos have a comfortable lead in terms of the business ecosystem. They have succeeded in creating one of the fastest growing ecosystems, reaching across all areas of society and significantly boosting financial inclusion, putting all 23 banks in Ghana onto a shared platform, and influencing the legislative framework of the country with their Mobile Money (MOMO). However, management, interoperability, an insufficient policy framework, a lack of regulation, and diverse thinking paradigms among participants in Ghana's many ecosystems are all obstacles to the development of the business ecosystem. The issues described in this research were addressed in this paper. Funding, human resources, digital platforms, and other key resources were cited as being critical for the effective development of Ghana's business environment. Finally, a compelling case has been made for the country to grow its local business ecosystems environment in order to create jobs and ensure sovereign security.

1. Senyo, P. K., Karanasios, S., Gozman, D., & Baba, M. (2022). FinTech ecosystem practices shaping financial inclusion: the case of mobile money in Ghana. European Journal of Information Systems, 31(1), 112-127;

2. Tobbin, P. (2011). Understanding the Mobile Money Ecosystem: Roles. Structure and Strategies.

3. Chen D, Vallespir B, Daclin N. An Approach for Enterprise Interoperability Measurement. MoDISE-EUS, 2008, p. 1-12.

4. Tsujimoto M, Kajikawa Y, Tomita J, Matsumoto Y. (2017) A review of the ecosystem concept - Towards coherent ecosystem desig. ;

5. Disrupt Africa. (2019). Fin novating for Africa 2019: Reimagining the African financial services landscape. Disrupt Africa;

6. Bank of Ghana. (2019). Payment systems statistics-first half 2019. https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/ uploads/2019/10/Payment-Systems-Statistics-FirstHalf-2019-Table.pd

7. Bank of Ghana (2020). Annual reports and Financial Statement https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/ uploads/2021/10/Payment-Systems-Statistics

8. Senyo, P. K., Liu, K., & Effah, J. (2019). Digital business ecosystem: Literature review and a framework for future research. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 52-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.002

9. Senyo, P. K., Osabutey, E. L. C., & Seny Kan, A. K. (2020). Pathways to improving financial inclusion through mobile money: A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. In Information Technology & People. https://doi. org/10.1108/ITP-06-2020-0418;

10. Suglobov A., Lobova S., Bogoviz A. (2021) Scenarios of future development of the modern digital economy: technical progress vs.: Modern Global Economic System: Evolutional Development vs. Revolutionary Leap. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems (LNNS, Volume 198). Cham, 2021. P. 1170-1178.

11. Iman, N. (2018). Is mobile payment still relevant in the FinTech era? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 30, 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap. 2018.05.009

12. Oborn, E., Barrett, M., Orlikowski, W., & Kim, A. (2019). Trajectory dynamics in innovation: Developing and transforming a mobile money service across time and place. Organization Science, 30(5), 1097-1123. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2018.1281

13. Moore, J. F. (2006). Business ecosystems and the view from the firm. The antitrust bulletin, 51(1), 31-75;

14. Wecht, C. H., Demuth, M., & Koppenhagen, F. (2021, November). Platform-Based Business Ecosystems-A Framework for Description and Analysis. In Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (pp. 92-100). Springer, Cham;

15. Moore, J. F. (2003). Digital business ecosystems in developing countries: An introduction. Berkman Center for Internet and Society, Harvard Law School. http://cyber. law. harvard. edu/bold/devel03/modules/episodeII. html.